Overappreciated arguments: Marr's three levels

🕑 11 min • 👤 Jon Rawski • 📆 January 12, 2020 in Discussions • 🏷 neuroscience, representations, Marr

<TG soapbox> The following is a guest post by Jon Rawski. I’m ruthlessly abusing my editorial powers to insert this reminder that the Outdex welcomes guest posts. Maybe you’d like to start a discussion on a topic that’s dear to your heart? Or maybe you have something to add to an ongoing discussion that can’t be fit in the comments section because it’s too long and involves multiple pictures and figures? Just send me your post in some editable format (not PDF) and I’ll try to post it asap. If you want to reduce the time from sending to posting, check the instructions on how to reduce the editorial load for me. Anyways, enough of my blabbering, let’s hear what Jon has to say… <TG soapbox/>

To spice up the Underappreciated Arguments series, I thought I’d describe a rhetorical chestnut beloved by many a linguist: Marr’s Three Levels. Anyone who has taken a linguistics class that dips a toe into the cognitive pool has heard of the Three Levels argument. It’s so ubiquitous that it’s been memed by grad students.

David Marr’s 1982 book Vision shows up in many a linguistics paper, some of which are seen in the JustMarrThings twitter account. Why is Marr everywhere? Most papers polled in that twitter account don’t have much to do with vision, much less neuroscience. Now, I’m not against citing Marr (1982), and I’m very sympathetic to the algorithmic lens. I just think the Three Levels are misinterpreted and overused, and this actually hinders linguist-neuroscientist integration. What better way to start a new decade than a rant, right? But since I’m not a total Grinch (garlic in my soul, three-decker sauerkraut and toadstool sandwich with arsenic sauce? no thanks), I’ll marshall a defense of Marr and insights for how linguists can talk more productively to neuroscientists.

Marr’s three levels/lenses

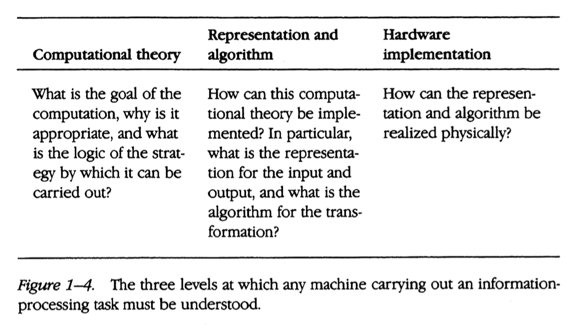

Marr’s contribution in Vision was to determine “the different levels at which an information processing device must be understood before one can be said to have understood it completely”. Marr suggested that explanation of information processing necessarily takes three forms. The most macro view is the computational theory level that defines the problem from an information processing perspective. Slightly more fine-grained, the Representations and algorithm level defines what representations the system uses and how it manipulates those representations. Subtle point: Marr considered representation to be a key element for understanding computation, but at the same level as algorithm. More fine-grained is the implementation level: how the information-processing model is solved biologically by cells, synapses, neuronal circuits, etc.

Personally, I tend to think of them as lenses. Each “level” is more or less refined, allowing different properties to emerge. For a delightful perspective, check out minutes 5-12 of this ’60s BBC episode (with soundtrack by Pink Floyd!).

This is a very general perspective on explanation in information processing. But I think the only reason linguists pay any attention to Marr is because he spends two paragraphs on how “Chomsky’s (1965) theory of transformational grammar is a true computational theory in the sense defined earlier”. He places Chomsky’s competence/performance distinction as the difference between the “computational theory” and “representation/algorithmic” levels. He even talks about trace theory a la Chomsky & Lasnik showing “some of the rather ad hoc restrictions that form part of the computational theory may be consequences of weaknesses in the computational power that is available for implementing syntactical decoding”. Linguists adapted this endorsement into the following argument (see above meme):

- Linguists’ take on Marr (very important apostrophe there!)

Marr distinguishes three levels of analysis of cognitive information-processing: computational, algorithmic, and implementational. Linguists work on the computational level, specifying the relevant representations and properties of language. We can’t care about algorithms and neural instantiations before understanding the computational level - and those are performance considerations really, we care about competence. In fact, perhaps neuroscientists should listen to linguists for what to look for first before they go looking in circuits for language stuff.

You can see variants of this argument in the Twitter account above. It is not productive. It alienates generative linguists from other linguists, and alienates linguists from neuroscientists. Lots of it stems from misunderstandings of these levels, but some of it is Marr’s fault.

Problems with the three levels

Why information processing?

My first gripe is that the whole thing comes from an information processing framework, which makes little sense neuronally or linguistically. Marr says “by taking an information-processing point of view, we have been able to formulate a rather clear overall framework for the process of vision”. But that was 1982. It’s not at all clear in 2020 that ‘information processing’, ‘encoding and decoding’, and the rest is an appropriate characterization either of linguistic cognition or brain function. We might just mean the narrow sense of Claude Shannon’s information theory, but I think most linguists would bristle at that. Shannon himself warned against bandwagoning, that information theory is “aimed in a very specific direction, a direction that is not necessarily relevant to such fields as psychology.”

Furthermore, while information theory is neutral to information content, that’s just not the case brain-wise. There is a simple reason: there is no such thing as invariant information content in a stimulus. Stimulus attributes are not objective physical characteristics of stimuli. How relevant a stimulus is instead depends on changing internal states coupled with experience. Taking a view of brain function as “Information processing” is irreconcilable with an internalist perspective. It confuses what you’re trying to explain with what you’re using to explain it. This is an underappreciated point noted also by some phoneticians (Hammarberg 1976; Hammarberg 1981). Information is not inherent in computation but becomes such when interpreted by an observer recognizing its significance. This means that a framework designed to understand ‘information processing’ misses the mark in terms of explanatory power either for language or brains. So when linguists say they work at a computational level defined in terms of information processing, they’re actually doing the opposite of what they’d like.

While I’m here, let me say something about representation. “Processing” has this annoying connotation of a procedure that takes a thing and turns it into another thing, or format transformation. “Information processing” relies on this connotation, tacitly implying representation is the end product. Linguists also accept this use when they talk about ‘representations’. But representation is not a thing! It is a process! Romain Brette gives very clear evidence of this, for brains and more generally. Read his BBS target article on it (Brette 2019), or his earlier “Philosophy of the spike” (Brette 2015).

Relationships matter more

My second gripe is that the three levels make little sense on their own, but the linguist argument behaves as though they do. I think this is mostly Marr’s fault, for saying things like “these three levels are coupled, but only loosely”. A big motivation for Marr was to clearly delineate computational and algorithmic/representational explanations. It’s obvious why. Numerous algorithmic models are compatible with a given computational problem. Explanation via algorithm is also useless unless you know what problem it solves, with which resources, and with what guarantees.

Here’s the problem, though, put clearly by Gyorgi Buzsaki in his new book. While numerous algorithmic models are compatible with a given computational problem, there’s evidence that only one or a few are compatible with those implemented by neuronal circuits. For example, in invertebrate neural circuits, like the crab somatogastric ganglion, there are only a handful of neurons, each of them different. Even though we’ve got the circuit wiring figured out, we don’t know the mechanisms that let the cell-to-cell interactions enable the sequential spatiotemporal patterns generating rhythmic output (Harris-Warrick, Marder, Selverston, and Moulins 1992; Marder, Goeritz, and Otopalik 2015). The degeneracy of this circuit is very rich, with hundreds of circuit solutions to the same rhythm in related species and within the members of the same species (Prinz, Bucher, and Marder 2004). Buzsaki says that because of this problem, “it is hard to find an impactful neuroscience experiment which is based on Marr’s suggested three-stage strategy”.

Yikes.

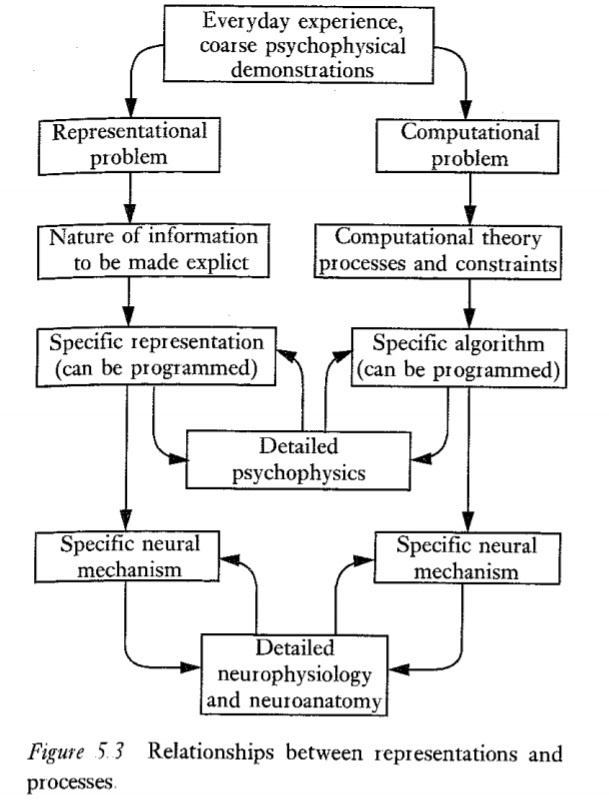

Later in the book, Marr is more expressive about explanatory relationships. Take a look at his diagram below. It’s hard to draw a three-way split there that resembles the Three Levels in a coherent way. Also notice that representation, which before was confined to the middle level as an object, now has its own flow. This makes a bit more sense under the representation-as-process view. However, I have an even harder time trying to fit modern linguistics into one level here.

In his afterward to the re-release of the book, Tommaso Poggio is critical of level independence. He recounts the gritty origin story of the Three Levels: while they were colleagues, Marr adapted the framework of Reichardt and Poggio (1976), which distinguished behavioral, algorithmic, and implementational levels (Marr swapped out ‘computation’ for behavior). Poggio notes that “one key aspect of the original argument disappeared in the process”. What was it? “It is necessary to study nervous systems at all levels simultaneously”. Great advice. Most computational neuroscientists understand this, and most comp neuro works in between levels, and doesn’t take any of them too seriously, which Poggio encourages. Linguists are shooting themselves in the foot by isolating linguistic insights to one Marr level, and alienating themselves to neuroscientists.

Moreover, Marr’s levels completely ignore the problem of learning. It’s bizarre that Marr omitted this, since learning was the focus of his famed work on the cerebellum and neocortex. This should put immediate red flags up to linguists, since a central motivation for structural and computational biases argued for in linguistics is to explain the initial knowledge state of a learner. Poggio also notes this, and argues for placing learning as another level, on top of computational theory, or as a part of each level. For him, “the problem of learning is at the core of the problem of intelligence and of understanding the brain”.

What is implementation?

An implication of the Three Levels argument is that linguists and psycholinguists get to talk about ‘neural implementation’ without being specific at all, or can just say ‘we need to have good representational theories first’. In practice this has resulted in waving away the hard problem that we actually want to solve. Yes, we’ve got things like localization of Merge to some part of the Inferior Frontal Gyrus, but as David Poeppel frequently points out, that’s a map of linguistic processes in the brain, not a mapping of processes to brain function. Furthermore, saying “neural circuits” or “the neural level” implements anything is misleading. Why? The “neural level” is an abstraction! Even “the neuron” itself is an abstraction!

Neurons have a stunningly varied morphology. How a single “neuron” computes is sufficiently complicated that Christof Koch wrote a whole book on “The Biophysics of Computation”. The last chapter, called “Unconventional Computing”, details how computation can even happen at the sub-neural level. It includes delightful sections like “Computing with Puffs of Gas” and “Programming with Peptides”. Randy Gallistel’s phenomenal book “Memory and the Computational Brain” ends with a chapter on “The Molecular Basis of Memory”. In fact, pick a neural entity at random and you’ll find work on how it computes. For example, concentration of free intracellular calcium in presynaptic terminals, dendrites, and cell bodies forms a variable that can act as memory, manipulated using buffers, calcium-dependent enzymes, and diffusion to instantiate specific computations. None of this is to say that circuits don’t compute. They can compute all sorts of things. But treating neural entities as implementations on a single level is extremely misleading.

Beyond The three levels

Okay, enough complaining. Marr did everyone a great service by centering computation as both a cognitive and neural problem. We know that what makes a mind/brain, what gives rise to human cognition, is a complex dynamical system — a massively parallel computer when the formal description is closer to the biophysical. It is also a rule-governed computer of discrete symbolic structures at a higher, more abstract level of description. How can we use both of these insights to move beyond the information-processing model, to properly reconcile the contributions of linguistics and neuroscience?

I think there are actually two questions here, and they each need to be present in every discussion. The best statement of them I can find comes from Smolensky and Legendre (2006). The question this whole post has been exploring is as follows

- The neural question for cognitive science

How are complex cognitive functions computed by a mass of numerical processors like neurons — each very simple, slow, and imprecise relative to the components that have traditionally been used to construct powerful, general-purpose computational systems? How does the structure arise that enables such a medium to achieve cognitive computation?

Smolensky & Legendre say this question is often confused with the cognitive question for neuroscience. That question asks for the cognitive significance of various biological components. To address it, a mathematical model of the mind/brain must be sufficiently faithful to the neurobiology to capture the role of each component in its biological system. At first glance, these two questions seem like they need to be answered by two different groups of people. Absolutely not. That’s the same mistake made in thinking Marr’s levels can be isolated. A linguist can very well ignore biological plausibility when generalizing linguistic principles. A linguist who cares about cognition cannot. If they do, they can guarantee that they’ll alienate themselves.

Marr’s computational centrality can be a great equalizer for linguists and neuroscientists. As someone who interacts daily with neuroscientists, when linguistic knowledge is framed computationally, they are hooked, and often surprised that linguists care about these things. Linguists have extremely good insights on problems neuroscientists care about, that they can’t get answers about from the psychologists. And they have many good insights on cognitive problems linguists care about but can’t answer using the tools they have. In my opinion, the 2020s should be the decade when linguists and neuroscientists should be working together as much as possible (and not just when we borrow their fMRI). This is extremely important given the rise of Distibuted Computation/Connectionism Part 2. Distributed Computation offers an idealized way to study the properties of a massively parallel computational system. Neuroscientists have already offered a lot there, and linguists can too. But this requires centering the computational properties of language, and not losing sight of the two questions mentioned above.

References

Brette, Romain. 2015. Philosophy of the spike: Rate-based vs. Spike-based theories of the brain. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 9. Frontiers.151.

Brette, Romain. 2019. Is coding a relevant metaphor for the brain? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Cambridge University Press.1–44.

Hammarberg, Robert. 1976. The metaphysics of coarticulation. Journal of phonetics 4. Elsevier.353–363.

Hammarberg, Robert. 1981. The cooked and the raw. Journal of Information Science 3. Sage Publications Sage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA.261–267.

Harris-Warrick, Ronald M, Eve Ed Marder, Allen I Selverston, and Maurice Ed Moulins. 1992. Dynamic biological networks: The stomatogastric nervous system. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Marder, Eve, Marie L Goeritz, and Adriane G Otopalik. 2015. Robust circuit rhythms in small circuits arise from variable circuit components and mechanisms. Current opinion in neurobiology 31. Elsevier.156–163.

Marr, David. 1982. Vision: A computational investigation into the human representation and processing of visual information. CUMINCAD.

Prinz, Astrid A, Dirk Bucher, and Eve Marder. 2004. Similar network activity from disparate circuit parameters. Nature neuroscience 7. Nature Publishing Group.1345.

Reichardt, Werner, and Tomaso Poggio. 1976. Visual control of orientation behaviour in the fly: Part i. A quantitative analysis. Quarterly reviews of biophysics 9. Cambridge University Press.311–375.

Smolensky, Paul, and Géraldine Legendre. 2006. The harmonic mind: From neural computation to optimality-theoretic grammar (cognitive architecture), vol. 1. MIT press.

Comments powered by Talkyard. Having trouble? Check the FAQ!